Serbia has been wandering about in terms of both foreign policy and security for over 30 years now. Officials say Serbia supports Ukraine's territorial sovereignty and integrity, but it only joined in on the condemnation of Russia at multilateral forums. Ultimately, if a foreign policy shift does come after the elections, the question is what its effects on democracy and media freedom in Serbia would be.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Serbia has been trying to balance and avoid joining the EU’s restrictive measures. Officials say Serbia supports Ukraine's territorial sovereignty and integrity, but it only joined in on the condemnation of Russia at multilateral forums. This position has been criticized by officials from certain EU countries, as well as influential public persons, mostly focusing on the idea that Serbia does not deserve a European perspective. Therefore, this short article aims to pinpoint the reasons behind Serbia’s position, as well as the perspectives that can be expected.

Serbia has been wandering about in terms of both foreign policy and security for over 30 years now. Regardless of the essential security and economic interests primarily related to the EU and the region, Southeast Europe, the legacy of the wars in Yugoslavia (primarily the 1999 NATO bombing), and above all, the still unresolved issue of Kosovo pushing Serbia into differentiating its foreign policy (the so-called “multi-vector policy”) and more active reliance and enhancement of ties with non-Western partners. Due to the ongoing status dispute with Prishtina, Serbia has given up the prospect of NATO integration in the past 15 years and it developed active ties with other powerful countries, primarily Russia and China, who are also permanent members of the UN Security Council. This policy was taken over by the current political elite which came into power in 2012.

Having signed the historic Brussels Agreement in 2013 on the normalization of relations with Kosovo, Serbia has started negotiations with the EU. However, in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and helped the rebel forces in Donbas, Serbia found itself in a political rift with the EU, refusing to comply with restrictive measures and stressing that it would do so anyway when EU accession is imminent. It was the Ukrainian crisis that has opened the way for Serbia to be perceived as a country that, although a candidate for membership, does not address the interests of the Union, hence the interpretation that it could potentially be a "Russian Trojan horse" within the EU. These interpretations gained momentum especially after the Russian aggression on Ukraine. However, the situation is somewhat more complex than it seems at first glance. Serbian-Russian relations are very complex, and so far, they have been dictated by the Kosovo dynamics, matters related to energy, as well as security aspects and the public opinion.

Not having a "compromise solution" for Kosovo which would be acceptable to citizens, with the perspective of EU membership growing ever more remote, primarily due to the low popularity of enlargement in some member states, the government has balanced its policy towards Moscow. Russia has undoubtedly been a great support to Serbia in international bodies in preventing Kosovo's accession to international organizations, as well as in the process of having certain states withdraw their recognition of Kosovo's independence. On the other hand, Russia has used the "Kosovo precedent" several times to justify its actions, justifying the recognition of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, the annexation of Crimea, and the recognition of Donetsk and Luhansk. This supports the thesis that Russian support for Serbia is essentially unprincipled, and that it is focused on achieving its realpolitik goals in a geopolitical context. Belgrade is well aware of this fact, as evidenced by the substantial distancing from Russia at a time when there was a possibility that Serbia's goal of reaching a "compromise solution" would be achieved with US support under Donald Trump. Namely, Serbia signed the so-called Washington agreement in September 2020 in the White House, which was reached without the involvement of Moscow, and which even compromised the relations between Serbia and China. That there are potential opportunities for weakening ties with Moscow if a "compromise solution for Kosovo" is reached is also suggested by the campaign of pro-government tabloids and televisions in which they accused the "Russian deep state" of organizing civil protests in early July 2020, which erupted due to the ad hoc implementation of measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. However, with Biden's victory, the prospects for reaching such an agreement under the auspices of the United States faded, and Serbia moved closer to Moscow again.

The next aspect is energy. Namely, Serbia has "bought" Russia's support since 2008 by selling NIS (Naftna industrija Srbije - Oil Industry of Serbia) to Russian Gazprom that same year, with the promise that the route of the new "Južni tok" (South Stream) gas pipeline would cross its territory. Several aspects of this energy agreement are challenging, but mostly because it cedes control over the oil and gas sector in Serbia to the Russians, as well as majority ownership of all energy-related joint ventures, which is a challenge when it comes to Serbia eventually joining the restrictive measures. The gas pipeline through the territory of Serbia was eventually built, but with a capacity four times lower than the original project. On the other hand, diversification of the gas supply hasn’t been achieved to this day, most likely due to the activities of pro-Russian players in Serbia and Bulgaria, which have been slowing down the construction of interconnectors between the two countries since 2014. In other words, Serbia can easily become the target of Russian energy blackmail, and Moscow has reduced gas supplies to Serbia after Putin's visit in 2014 (allegedly due to arrears), showing that gas can be weaponized. Hoping that it would be getting cheaper gas, Serbia has also built a significant gas infrastructure in the past four years, thus increasing its imports, meaning that Serbia is now even more exposed to possible pressure from Russia than before. Having in mind that Serbia has to negotiate a new long-term agreement on natural gas supply with Russia after the upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections makes the question of gas import even more important.

Since 2013 Serbia has been strengthening its security cooperation with NATO through the Partnership for Peace program, but it has been doing the same with Russia - Serbia accepted observer status in the CSTO and takes part in military exercises, it has opened a Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center (RSHC) in Niš in 2013 after five years of delays, although it still hasn’t been given diplomatic status, nor did Serbia agree to open a Russian liaison office at the Ministry of Defense, despite constant pressure from Moscow. Also, the import of Russian weapons and military equipment is not very important, regardless of the media space the topic received, since a large part of the used equipment being imported has a limited shelf life and will soon have to be replaced. But certainly, this cooperation has left significant consequences on the international perception of Serbia's position, as well as internal discourse.

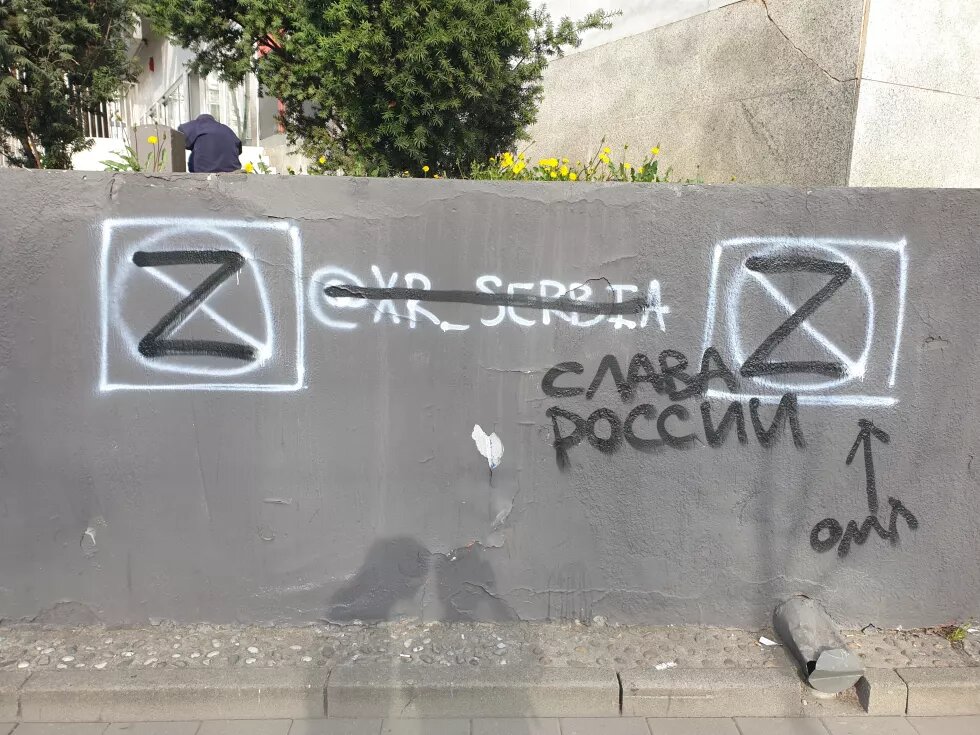

Certainly, the most critical element is the issue of Russia's presentation in the media. From 2008 onwards, citizens have been flooded with information about the importance of Russia and the desirability of Russian-Serbian cooperation, with negative reporting on NATO and mostly neutral reporting on the EU. Since the current ruling elite came to power, disinformation has been raised to a higher level, with a number of pro-government tabloids and television stations leading the way, including several with a national frequency. Independent research shows that there was almost no negative coverage of Russia and Putin in the mainstream media in Serbia. It is interesting that such news is mostly domestic production, i.e., that it is processed news from Russian and other sources adjusted to domestic "needs". It is evident that there is no Russian criticism of the Serbian ruling elite whatsoever in the discourse produced by this media, while it often appears in the media. In other words, the pro-Russian disinformation campaign is huge, but carried out in such a way as to maintain the appearance of strong relations between Serbia and Russia, although the closeness is questionable. The question of the reason for such actions remains. The most probable answer is that in this way, the challenges "from the right" imposed on the ruling elite are neutralized, especially the main party in power – SNS, since right-wing voters, who often cultivate pro-Russian sentiments, are their primary electorate. A large number of citizens (who mostly have negative sentiments towards NATO) interpret the war in Ukraine as a conflict between Ukraine, which has been manipulated by NATO, and Russia. Therefore, a challenge coming from the right from another Russian-backed political option could likely significantly jeopardize the ruling party's "catch-all" approach, which is especially important ahead of the upcoming elections when the SNS and its president Aleksandar Vučić will strive to cement their rule for the following period.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine came at the worst time possible for the ruling elite in Serbia. The election campaign is underway, energy dependence on Russia is huge, and the desired compromise solution on Kosovo is far away (if it ever comes). An immediate decoupling from Russia, and joining in on sanctions against it, would probably create a huge rift in society, which would be difficult to control. The public, which has been flooded with misinformation about Russia, should still be prepared for a step that would be completely opposite from everything promoted so far. Serbia’s foreign policy must shift, and the question is how big of a turn it can be. Ultimately, if a foreign policy shift does come after the elections, the question is what its effects on democracy and media freedom in Serbia would be.