There are more than 2,000 memorials and statues across Kosovo related to the 1998–99 war, but the authorities lack proper legal guidelines to deal with the chaotic construction of monuments.

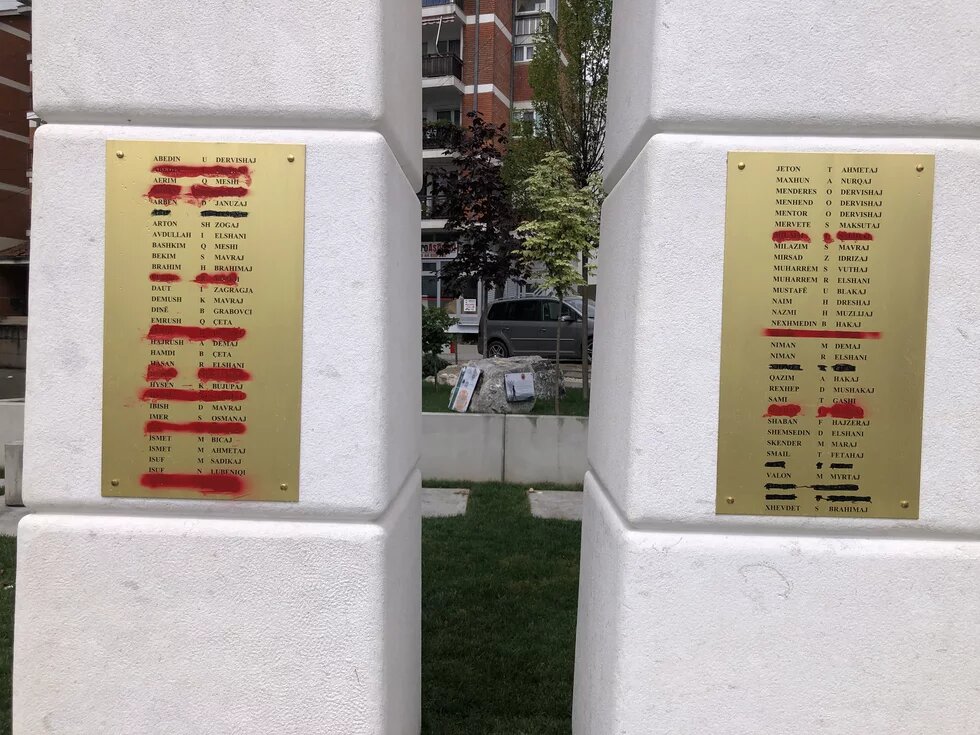

For more than two years, a memorial erected in honor of guerrilla fighters in the western Kosovo town of Istog/Istok has remained contested, with plaques defaced by red spray paint and black marker where several deceased guerrillas’ names have been crossed out.

A dispute over the inclusion of civilians’ names on a monument dedicated to fallen fighters in this small town highlights a broader problem in Kosovo, the widespread erection of war memorials without any clear or regulated process.

“This is an illustration of some people thirsting for glory, a false glory,” says Fikret Shatri, a former KLA guerrilla fighter. “This is an abuse of public space in the name of war and freedom.” The monument, installed in 2023 in the town center, consists of two white columns topped with the Kosovo Liberation Army insignia. The memorial includes two plaques listing 13 more names than the previous one, all civilians, war victims who were never officially registered as KLA members.

Some former fighters, including Shatri, opposed this addition and covered the names of those they said were not combatants with red paint. The monument has remained in this state for three years, symbolizing the disputes surrounding many of the war memorials built across Kosovo. As in Istog/Istok, numerous memorials and statues commemorating the 1998–99 war have been placed throughout Kosovo, raising the question: who decides which statues are commissioned for public spaces?

In Kosovo, there are no general rules for commissioning statues. Decisions are usually left to individual councils of war veterans. Most statues are publicly funded, but there is no planning committee to assess whether a memorial is appropriate for its location, of sufficient quality, or whether the person being commemorated is suitable for such an honor.

The Kosovo Memorial Complex Management Agency has not responded regarding what should be done with the contested memorial in Istog/Istok. Ilir Ferati, the mayor of Istog/Istok, said the municipality had no role in approving this particular memorial. “There was no debate in the municipal assembly about the installation of the memorial,” he said.

“A garden of statues”

An 11-week NATO bombing campaign drove Serbian forces from Kosovo and halted a wave of massacres and ethnic cleansing against ethnic Albanians in what was then a southern province of Serbia. Although most people killed in the 1998–99 war were civilians, most war memorials commemorate freedom fighters.

In the center of the western Kosovo town of Decan/Deçan stand five statues of fallen Kosovo Liberation Army fighters, who are regarded in the country as heroes of the war for liberation from Serbian rule. But one of the statues actually honors a man who was killed in 2015, more than a decade and a half after the war ended. Beg Rizaj died in May 2015 during a two-day firefight between police and a large group of ethnic Albanian gunmen that left 22 people dead in the town of Kumanovo, in neighboring North Macedonia.

A joint statement issued by Kosovo’s president, Atifete Jahjaga and prime ministër, Isa Mustafa, at the time condemned any “involvement of citizens of Kosovo in the Macedonia incidents.” The others from that group were buried in the cemetery dedicated to martyrs in Pristina. The surviving gunmen were later convicted of terrorism.

Rizaj’s statue in Deçan/Decane was not commissioned by the Kosovo authorities but was an independent initiative of his former KLA comrades.

In 2018, Ramush Haradinaj, then prime minister, attended the inauguration of Rizaj’s statue, who had served under his command in this region of Kosovo during the war. His government also provided financial assistance to the families of those involved in the Kumanovo incident. Bashkim Ramosaj, the mayor of the Decan/Deçan municipality, confirmed that the statue was erected in 2018 by a group of war veterans, and that the local assembly had no objection to its installation in the town square.

“ There is still an informal power of war veterans in establishing memorials and setting criteria and its hard to challnge it,” said Nora Ahmetaj a transitional justice researcher. The tiny country is dotted with traces of the Balkans’ recent turbulent past, each bearing the weight of its own time.

Bislim Zogaj, the former director of the Agency for the Management of Memorial Complexes of Kosovo, said there is a legal vacuum regarding decision-making for the placement of statues, which often results in a lack of proper criteria.

“There are cases where city squares resemble gardens of statues that are difficult to challenge because of the sensitivity surrounding the war and the fallen,” Zogaj said. He added that there is still little space for civilian victims. “Kosovo lacks a memorial for children which is not realized yet due to proper planing, while for a long time it was easy to place statues anywhere without any site-specific planning or legal compliance,” he said.

Heroes and Misplaced Memorials

Only one memorial, dedicated to former Albanian guerrilla commander Adem Jashari, was erected in the southern Kosovo city of Prizren, but it was later removed following public outcry over the criteria for its construction.

Zogaj said that many statues have been installed even after the adoption of the relevant law, and that removing them is often difficult. “It causes a lot of tension and anger, but work must be done to curb it and to prevent such cases from happening again,” he said. In some cases, new memorials have replaced older ones, mainly from the Yugoslav era. Some public artworks that gained prominence during Yugoslav times, once celebrated as symbols of unity and progres such as the “Brotherhood and Unity” memorial commemorating Albanian and Serb partisans who fought together during World War II, were removed in the aftermath of the Kosovo war.

Architect Arber Shita said that more precise legislation is needed to determine who decides which statues are commissioned for public spaces, particularly when it comes to design, cultural, and social relevance. “Many statues and memorials were erected, often in the wrong places. But there are also examples where memorials have been created through a very careful and professional process,” he said. While recent history and the war are prominently represented, minorities in Kosovo feel underrepresented in the dominant culture of memorialization.

Bashkim Ibishi, director of the Pristina-based organization Advanced Together, which advocates for minority rights, said that public memory of the Kosovo war has been built around the Albanian majority excluding largely the Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptian communities who also faced violence before, during, and after the war.

“The lack of inclusiveness in the culture of remembrance has contributed to the deepening marginalization and stigmatization of those groups, social fragmentation, the fueling of identity and ethnic politics, and a weakened ability of society to learn from past injustices,” Ibishi said.