In Kosovo, a veil of silence has systematically obscured the reality of wartime sexual violence, while only a few memorialization initiatives have sought to expose these crimes and affirm survivors’ experiences.

On the afternoon of June 27, 1999, Zeke Ceku entered Pristina’s Grand Hotel for the first time in nearly a decade. The war had officially ended two weeks earlier, after 78 NATO airstrikes aimed at halting atrocities and the ethnic cleansing of civilians carried out by Serbian forces in their brutal counter-insurgency war against ethnic Albanian guerrillas of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA).

A former hotel employee, Ceku had returned to take over management of the public hotel company from the remaining Serb staff. After a brief tour of most of the hotel’s floors, he went down to the sports and ping-pong hall.

“There was a lot of women’s underwear in the room, a lot of blood stains, some bottles of alcohol, cigarette butts, and ropes,” he recalls. “There were clear signs of sexual violence.”

But his account has no surviving evidence, not even a photograph. “The place was cleaned up by KFOR soldiers. Of course, they have the evidence,” Ceku says.

This year, for the first time, the command of Kosovo’s peacekeeping mission announced that, by decision of NATO headquarters, the archives would be opened to Kosovo institutions. Ceku believes this evidence should be requested and preserved for memorialization.

Sites of trauma and absence of memory

As at the Grand Hotel, and at hundreds of other sites where survivors and witnesses reported mass sexual violence and sexual slavery, no trace or marker commemorates what happened. Despite the widespread use of sexual violence during the 1998–99 war in Kosovo, it has rarely been acknowledged in public memorials.

Prevailing practices of war commemoration largely silence conflict-related sexual violence. Among survivors and within society, it remains cloaked in a culture of silence. This reality was partly the result of how rape was perceived within society. After the war, many, including political and KLA fighters, regarded it as a sign of weakness and a source of humiliation for families. In a patriarchal context, silence itself became a mechanism to conceal what was seen as the darkest "stain" on the glory of fighting for freedom.

Kadire Tahiraj, who runs the Center for Women’s Rights in Drenas/ Glogovac, an organization providing psychosocial and economic support to survivors of sexual violence, says the trauma has long been perceived as a private burden. “The violence they experienced makes them see this trauma as something personal, a sense of shame considered unsuitable for public representation or remembrance,” she explains. During the war, other public buildings were also used as sites of torture and sexual violence, leaving a permanent mark for those who endured such atrocities.

H. B., a survivor of sexual violence who wished to be identified only by her initials, recalls April 16, 1999, when she was taken to a textile factory in Gjakova. There, she encountered other women and girls, including minors.

“I never want to go near that area. It always reminds me of that horror. I try to avoid it as much as I can,” she says.

She adds that she would not want to see any inscription explaining what happened there. “The building itself reminds me of it, let alone any explanation.”

Like her thousands of other women were also victims of sexual violence inflicted by Serbian forces during the Kosovo war of 1998-99. To date, 2,107 people have applied to the government’s Commission to Recognise and Verify Survivors of Sexual Violence During the Kosovo War for official recognition of their status, yet only three women have ever spoken publicly about their experiences. Numerous factors contribute to this conspiracy of silence, particularly the stigma and lack of support from families and their circles. In the first years after the war, there was a pact of silence, as many men abandoned their wives who had been raped, leading to the breakdown of numerous families.

Commemorating sexual violence must therefore respect survivors’ wishes, while also recognizing that the silence reflects their anger at the absence of justice and the enduring stigma they face. Furthermore, such memorials both honor survivors’ experiences and recognize the intergenerational consequences of such violence. Naime Sherifi, a human rights activist who has long worked with survivors of sexual and domestic violence, points out that few memorials speak about women, let alone their struggles for justice. “I think memorialization of sexual violence needs to be very careful not to aggravate the victims, but we need to think further about future generations, about history,” she says.

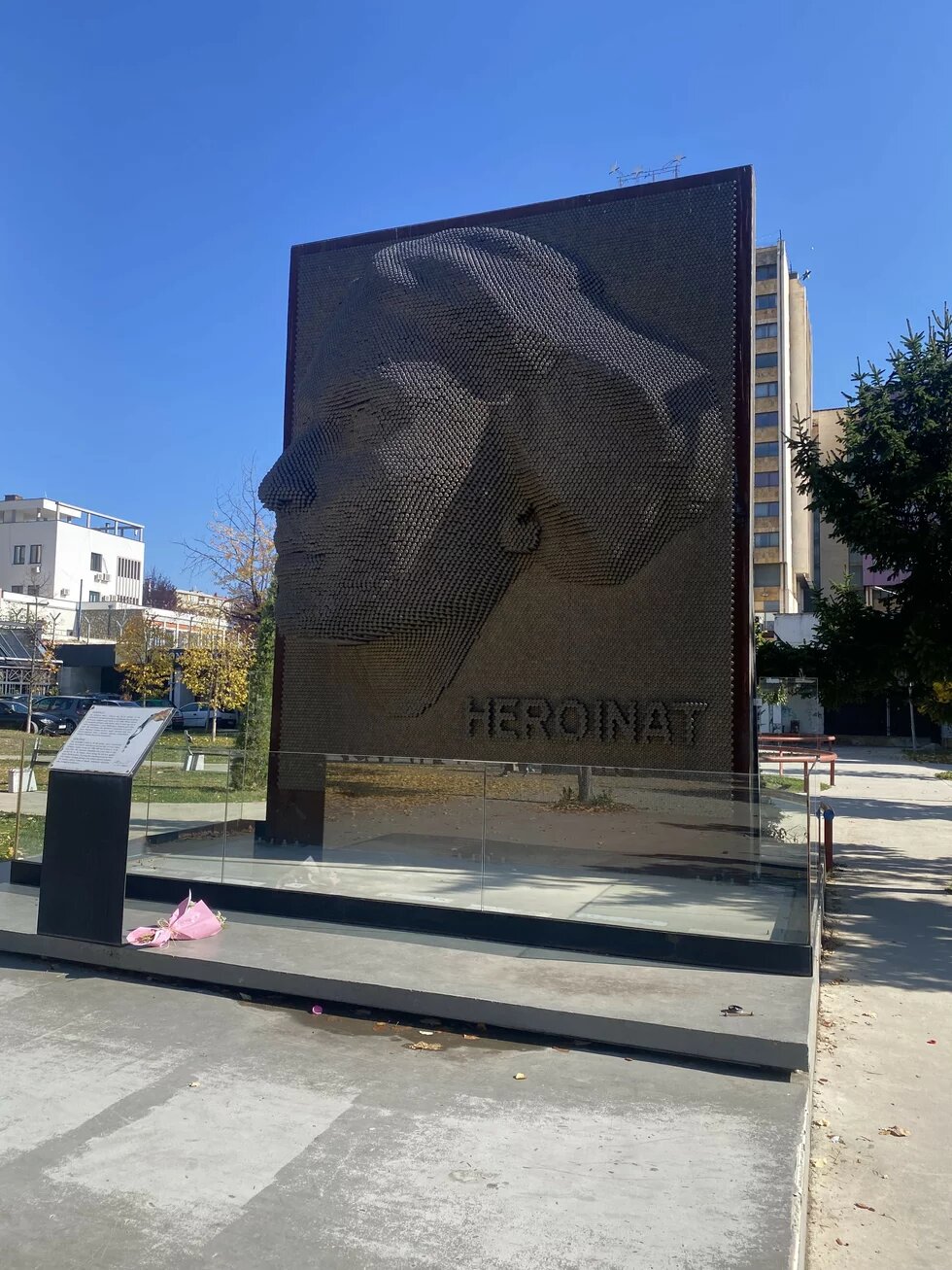

Numerous memorials in Kosovo commemorate victims of war, but only one specifically honors a large group of survivors of wartime rape.

That memorial, Heroinat, remains the only public monument of its kind. However, in recent years, there has been some memorialization initiatives outside public spaces, such as the Museum of Sexual Violence Moment by the Jahjaga Foundation, or Alketa Xhafa Mripa's installation Thinking of You, dedicated to survivors of sexual violence in war, first displayed in 2015 in Pristina and later at the Council of Europe.

Bringing hidden histories into public space

The Heroinat Memorial, unveiled on June 12, 2015, the sixteenth anniversary of Pristina’s liberation, comprises 20,000 pins that contour the face of a woman symbolizing survivors of sexual violence during the 1999 Kosovo War. The use of pins marks a departure from traditional heroic iconography. Alma Lama, a former MP and diplomat now a civil society activist who initiated the installation of the “Heroinat” memorial, says that representing victims of sexual violence in memorials challenges a long-standing tradition by giving visibility to women.

“The presence of these memorials in public spaces not only encourages people to recognize sexual violence as an issue that requires public discussion, but also helps normalize conversations about sexual violence in war,” Lama explains. But Lama says the memorial as a whole represents and acknowledges women’s diverse experiences and contributions to freedom, not only those related to sexual violence. I asked for the dedication on the plaque to be changed, because it is dedicated to all women,’ she says. Efforts to memorialise wartime rape in Kosovo took a significant step forward last year with the opening of the Kosovo War Rape Survivors Museum in the capital, Pristina, by the Jahjaga Foundation of former Kosovo President Atifete Jahjaga. “Museums, memorials, and installations offer a gentler but powerful way of raising awareness in society about wartime rape, by making the issue more tangible for those who have not experienced war,” said museum coordinator Bleona Hajdari.

Two years ago, the Faculty of Law at the University of Prishtina, the country’s largest public university, launched an initiative to create a memorial corner dedicated to survivors of sexual violence within its building. The dean of the faculty, Avni Puka, explained that they are “in coordination with the Ministry of Culture to create a memorial space within the faculty building.”

To counter the culture of silence, experts stress that memorials must be explicitly dedicated to eradicating sexual violence in war.

In Kosovo, as in most post-conflict countries of the former Yugoslavia, practical mechanisms for survivor-driven memorialization remain underdeveloped. In Bosnia, even after three decades, only recently have the house on Pionirska Street in Visegrad, where systematic rape occurred, and the Partizan sports hall in Foca, used as a rape camp, been marked as sites of violence.

Arsim Bajram, Univeristy Professor of Law and a member of the Kosovo Academy of Sciences who has been involved in several of the country’s transitional justice institutions, highlights the importance of remembrance:

“By transforming sites of trauma into places of reflection and support, these memorials help shape a memory that resists fading with time,” he says.